WINE

Plavac Mali Decoded: Your Ultimate Guide

Dive into a comprehensive exploration revealing all you need to know about the most popular Croatian red wine - Plavac Mali.

Exploring Dalmatian Cuisine: Pairing Food and Wine

Get ready for an unforgettable journey as our guide to Dalmatian food and wine pairing leads you through matching the perfect wines with Dalmatia's authentic dishes!

Croatian Pinot Gris Food Pairing Explained

Explore the world of Croatian Pinot Gris food pairing with our comprehensive guide! Learn how to pair it with various types of dishes and flavors.

5 Delicious Food Pairings with Croatian Blaufrankisch

Explore the world of Croatian Blaufränkisch wine and discover perfect food pairings. Dive into its unique earthy minerality and balanced structure and learn how to pair it with amazing dishes!

Uncover Korčula: Where White Wines Reign Supreme

Maybe, like many people, you're yearning for a taste that goes beyond the usual reds and Chardonnays. In Croatia's sunny Dalmatia, there's an island with rich connections to winemaking and a variety of white wines waiting to be explored.

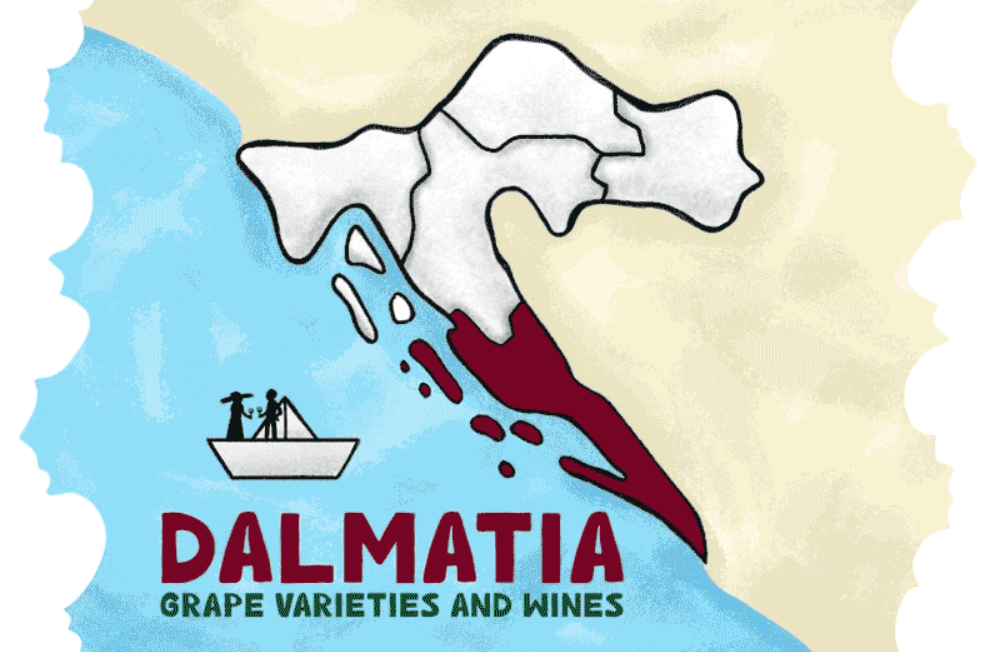

Ultimate Guide to 16 Unique Dalmatian Wine Varieties

Explore the rich biodiversity of Dalmatian grape varieties and Croatian wine, highlighting their distinctiveness.

Sipping Like a Local: The Ultimate Guide to Croatian Summer Drinks

From daily routines to notable occasions, Croatian drinks encapsulate the essence of local customs and warmth. Whether savouring wine along the Adriatic shores or sharing rakija among companions, each beverage narrates a tale of tradition and creativity interwoven into the Croatian way of life.

Croatian Sylvaner Wine: Overlooked White Jewel

Discover your next favorite Croatian white wine - Sylvaner! Known as Silvanac Zeleni in Croatian, a quietly captivating grape variety rooted in Central Europe's heartland is an overlooked white jewel.

Perfect Croatian Wines to Warm Your Soul

Lets embarking on a journey to discover the ultimate Croatian wines that will warm your soul but also transform your winter evenings into cozy, memorable experiences!

Enosophia: Exploring Wine Closure Options

Ever questioned the choices between cork and screw cap closures? Embark on our exploration of wine closures for a nuanced perspective on their pros and cons.